New research into a notorious Eastern European organized cybercrime

gang accused of stealing more than $100 million from banks and

businesses worldwide provides an unprecedented, behind-the-scenes

look at an exclusive “business club” that dabbled in cyber espionage and

worked closely with phantom Chinese firms on Russia’s far eastern

border.

In the summer of 2014, the U.S. Justice Department joined multiple international law enforcement agencies and security firms in taking down the Gameover ZeuS botnet, an ultra-sophisticated, global crime machine that infected upwards of a half-million PCs.

Thousands of freelance cybercrooks have used a commercially available form of the ZeuS banking malware for years to siphon funds from Western bank accounts and small businesses. Gameover ZeuS, on the other hand, was a closely-held, customized version secretly built by the ZeuS author himself (following a staged retirement) and wielded exclusively by a cadre of hackers that used the systems in countless online extortion attacks, spam and other illicit moneymaking schemes.

Last year’s takedown of the Gameover ZeuS botnet came just months after the FBI placed a $3 million bounty on the botnet malware’s alleged author — a Russian programmer named Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev who used the hacker nickname “Slavik.” But despite those high-profile law enforcement actions, little has been shared about the day-to-day operations of this remarkably resourceful cybercrime gang.

That changed today with the release of a detailed report from Fox-IT, a security firm based in the Netherlands that secretly gained access to a server used by one of the group’s members. That server, which was rented for use in launching cyberattacks, included chat logs between and among the crime gang’s core leaders, and helped to shed light on the inner workings of this elite group.

The chat logs show that the crime gang referred to itself as the “Business Club,” and counted among its members a core group of a half-dozen people supported by a network of more than 50 individuals. In true Oceans 11 fashion, each Business Club member brought a cybercrime specialty to the table, including 24/7 tech support technicians, third-party suppliers of ancillary malicious software, as well as those engaged in recruiting “money mules” — unwitting or willing accomplices who could be trained or counted on to help launder stolen funds.

“To become a member of the business club there was typically an initial membership fee and also typically a profit sharing agreement,” Fox-IT wrote. “Note that the customer and core team relationship was entirely built on trust. As a result not every member would directly get full access, but it would take time until all the privileges of membership would become available.”

Michael Sandee, a principal security expert at Fox-IT and author of the report, said although Bogachev and several other key leaders of the group were apparently based in or around Krasnodar — a temperate area of Russia on the Black Sea — the crime gang had members that spanned most of Russia’s 11 time zones.

Geographic diversity allowed the group — which mainly worked regular 9-5 hour days Monday through Friday — to conduct their cyberheists against banks by following the rising sun across the globe — emptying accounts at Australia and Asian banks in the morning there, European banks in the afternoon, before handing the operations over to a part of the late afternoon team based in Eastern Europe that would attempt to siphon funds from banks that were just starting their business day in the United States.

“They would go along with the time zone, starting with banks in Australia, then continuing in Asia and following the business day wherever it was, ending the day with [attacks against banks in] the United States,” Sandee said.

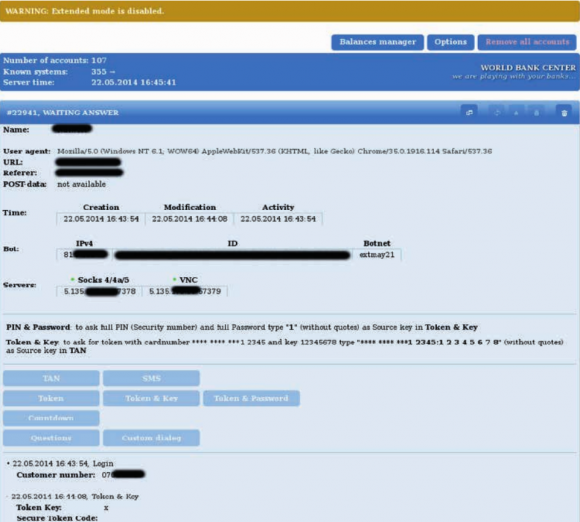

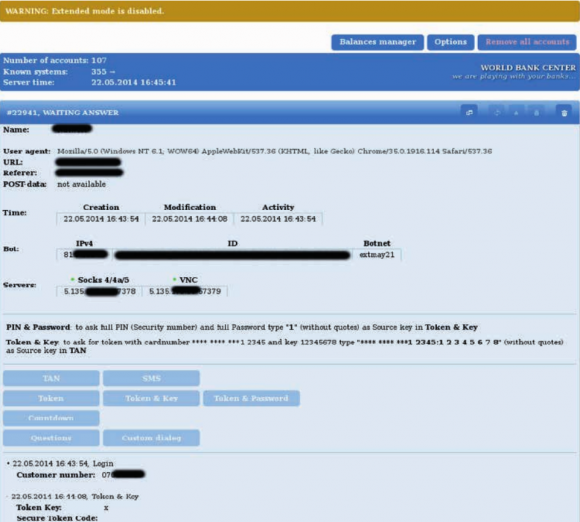

Business Club members who had access to the GameOver ZeuS botnet’s panel for hijacking online banking transactions could use the panel to intercept security challenges thrown up by the victim’s bank — including one-time tokens and secret questions — as well as the victim’s response to those challenges. The gang dubbed its botnet interface “World Bank Center,” with a tagline beneath that read: “We are playing with your banks.”

CHINESE BANKS, RUSSIAN BUSINESSES

CHINESE BANKS, RUSSIAN BUSINESSES

Aside from their role in siphoning funds from Australian and Asian banks, Business Club members based in the far eastern regions of Russia also helped the gang cash out some of their most lucrative cyberheists, Fox-IT’s research suggests.

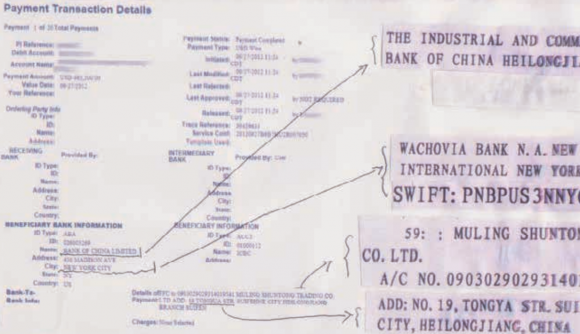

In April 2011, the FBI issued an alert warning that cyber thieves had stolen approximately $20 million in the year prior from small to mid-sized U.S. companies through a series of fraudulent wire transfers sent to Chinese economic and trade companies located on or near the country’s border with Russia.

In that alert, the FBI warned that the intended recipients of the fraudulent, high-dollar wires were companies based in the Heilongjiang province of China, and that these firms were registered in port cities located near the Russia-China border. The FBI said the companies all used the name of a Chinese port city in their names, such as Raohe, Fuyuan, Jixi City, Xunke, Tongjiang, and Donging, and that the official name of the companies also included the words “economic and trade,” “trade,” and “LTD”. The FBI further advised that recipient entities usually held accounts with a the Agricultural Bank of China, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and the Bank of China.

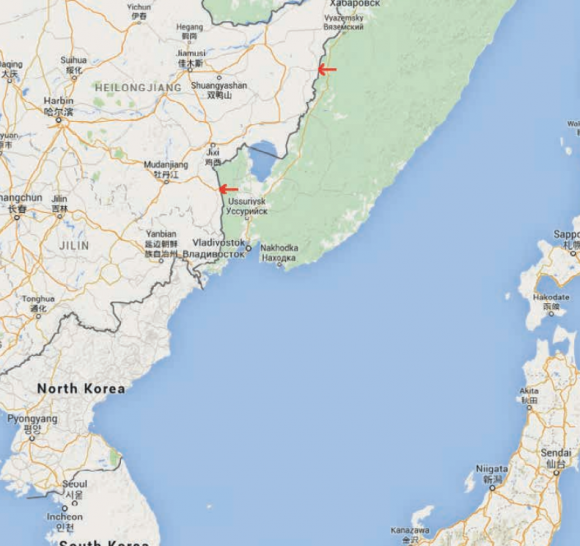

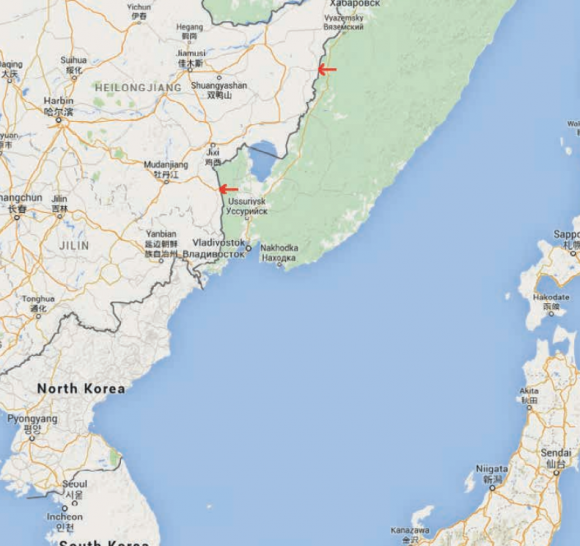

Fox-IT said its access to the gang revealed documents that showed members of the group establishing phony trading and shipping companies in the Heilongjiang province — Raohe county and another in Suifenhe — two cities adjacent to a China-Russia border crossing just north of Vladivostok.

Sandee said the area in and around Suifenhe began to develop several

major projects for economic cooperation between China and Russia

beginning in the first half of 2012. Indeed, this Slate story

from 2009 describes Suifenhe as an economy driven by Russian shoppers

on package tours, noting that there is a rapidly growing population of

Russian expatriates living in the city.

“So it is not unlikely that peer-to-peer ZeuS associates would have made use of the positive economic climate and business friendly environment to open their businesses right there,” Fox-IT said in its report. “This shows that all around the world Free Trade Zones and other economic incentive areas are some of the key places where criminals can set up corporate accounts, as they are promoting business. And without too many problems, and with limited exposure, can receive large sums of money.”

KrebsOnSecurity publicized several exclusive stories about U.S.-based

businesses robbed of millions of dollars from cyberheists that sent the

stolen money in wires to Chinese firms, including $1.66M in Limbo After FBI Seizes Funds from Cyberheist, and $1.5 million Cyberheist Ruins Escrow Firm.

KrebsOnSecurity publicized several exclusive stories about U.S.-based

businesses robbed of millions of dollars from cyberheists that sent the

stolen money in wires to Chinese firms, including $1.66M in Limbo After FBI Seizes Funds from Cyberheist, and $1.5 million Cyberheist Ruins Escrow Firm.

KEEPING TABS ON THE NEIGHBORS

KEEPING TABS ON THE NEIGHBORS

The Business Club regularly divvied up the profits from its cyberheists, although Fox-IT said it lamentably doesn’t have insight into how exactly that process worked. However, Slavik — the architect of ZeuS and Gameover ZeuS — didn’t share his entire crime machine with the other Club members. According to Fox-IT, the malware writer converted part of the botnet that was previously used for cyberheists into a distributed espionage system that targeted specific information from computers in several neighboring nations, including Georgia, Turkey and Ukraine.

Beginning in late fall 2013 — about the time that conflict between Ukraine and Russia was just beginning to heat up — Slavik retooled a cyberheist botnet to serve as purely a spying machine, and began scouring infected systems in Ukraine for specific keywords in emails and documents that would likely only be found in classified documents, Fox-IT found.

“All the keywords related to specific classified documents or Ukrainian intelligence agencies,” Fox-IT’s Sandee said. “In some cases, the actual email addresses of persons that were working at the agencies.”

Likewise, the keyword searches that Slavik used to scourt bot-infected systems in Turkey suggested the botmaster was searching for specific files from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Turkish KOM – a specialized police unit. Sandee said it’s clear that Slavik was looking to intercept communications about the conflict in Syria on Turkey’s southern border — one that Russia has supported by reportedly shipping arms into the region.

“The keywords are around arms shipments and Russian mercenaries in Syria,” Sandee said. “Obviously, this is something Turkey would be interested in, and in this case it’s obvious that the Russians wanted to know what the Turkish know about these things.”

According to Sandee, Slavik kept this activity hidden from his fellow Business Club members, at least some of whom hailed from Ukraine.

“The espionage side of things was purely managed by Slavik himself,” Sandee said. “His co-workers might not have been happy about that. They would probably have been happy to work together on fraud, but if they would see the system they were working on was also being used for espionage against their own country, they might feel compelled to use that against him.”

Whether Slavik’s former co-workers would be able to collect a reward even if they did turn on their former boss is debatable. For one thing, he is probably untouchable as long as he remains in Russia. But someone like that almost certainly has protection higher up in the Russian government.

Indeed, Fox-IT’s report concludes it’s evident that Slavik was involved in more than just the crime ring around peer-to-peer ZeuS.

“We could speculate that due to this part of his work he had obtained a level of protection, and

was able to get away with certain crimes as long as they were not committed against Russia,” Sandee wrote. “This of course remains speculation, but perhaps it is one of the reasons why he has as yet not been apprehended.”

The Fox-IT report, available here (PDF), is the subject of a talk today at the Black Hat security conference in Las Vegas, presented by Fox-IT’s Sandee, Elliott Peterson of the FBI, and Tillmann Werner of Crowdstrike.

In the summer of 2014, the U.S. Justice Department joined multiple international law enforcement agencies and security firms in taking down the Gameover ZeuS botnet, an ultra-sophisticated, global crime machine that infected upwards of a half-million PCs.

Thousands of freelance cybercrooks have used a commercially available form of the ZeuS banking malware for years to siphon funds from Western bank accounts and small businesses. Gameover ZeuS, on the other hand, was a closely-held, customized version secretly built by the ZeuS author himself (following a staged retirement) and wielded exclusively by a cadre of hackers that used the systems in countless online extortion attacks, spam and other illicit moneymaking schemes.

Last year’s takedown of the Gameover ZeuS botnet came just months after the FBI placed a $3 million bounty on the botnet malware’s alleged author — a Russian programmer named Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev who used the hacker nickname “Slavik.” But despite those high-profile law enforcement actions, little has been shared about the day-to-day operations of this remarkably resourceful cybercrime gang.

That changed today with the release of a detailed report from Fox-IT, a security firm based in the Netherlands that secretly gained access to a server used by one of the group’s members. That server, which was rented for use in launching cyberattacks, included chat logs between and among the crime gang’s core leaders, and helped to shed light on the inner workings of this elite group.

The

alleged ZeuS Trojan author, Yevgeniy Bogachev, Evgeniy Mikhaylovich

Bogachev, a.k.a. “lucky12345″, “slavik”, “Pollingsoon”. Source: FBI.gov

The chat logs show that the crime gang referred to itself as the “Business Club,” and counted among its members a core group of a half-dozen people supported by a network of more than 50 individuals. In true Oceans 11 fashion, each Business Club member brought a cybercrime specialty to the table, including 24/7 tech support technicians, third-party suppliers of ancillary malicious software, as well as those engaged in recruiting “money mules” — unwitting or willing accomplices who could be trained or counted on to help launder stolen funds.

“To become a member of the business club there was typically an initial membership fee and also typically a profit sharing agreement,” Fox-IT wrote. “Note that the customer and core team relationship was entirely built on trust. As a result not every member would directly get full access, but it would take time until all the privileges of membership would become available.”

Michael Sandee, a principal security expert at Fox-IT and author of the report, said although Bogachev and several other key leaders of the group were apparently based in or around Krasnodar — a temperate area of Russia on the Black Sea — the crime gang had members that spanned most of Russia’s 11 time zones.

Geographic diversity allowed the group — which mainly worked regular 9-5 hour days Monday through Friday — to conduct their cyberheists against banks by following the rising sun across the globe — emptying accounts at Australia and Asian banks in the morning there, European banks in the afternoon, before handing the operations over to a part of the late afternoon team based in Eastern Europe that would attempt to siphon funds from banks that were just starting their business day in the United States.

“They would go along with the time zone, starting with banks in Australia, then continuing in Asia and following the business day wherever it was, ending the day with [attacks against banks in] the United States,” Sandee said.

Image: Timetemperature.com

Business Club members who had access to the GameOver ZeuS botnet’s panel for hijacking online banking transactions could use the panel to intercept security challenges thrown up by the victim’s bank — including one-time tokens and secret questions — as well as the victim’s response to those challenges. The gang dubbed its botnet interface “World Bank Center,” with a tagline beneath that read: “We are playing with your banks.”

The business end of the Business Club’s peer-to-peer botnet, dubbed “World Bank Center.” Image: Fox-IT

Aside from their role in siphoning funds from Australian and Asian banks, Business Club members based in the far eastern regions of Russia also helped the gang cash out some of their most lucrative cyberheists, Fox-IT’s research suggests.

In April 2011, the FBI issued an alert warning that cyber thieves had stolen approximately $20 million in the year prior from small to mid-sized U.S. companies through a series of fraudulent wire transfers sent to Chinese economic and trade companies located on or near the country’s border with Russia.

In that alert, the FBI warned that the intended recipients of the fraudulent, high-dollar wires were companies based in the Heilongjiang province of China, and that these firms were registered in port cities located near the Russia-China border. The FBI said the companies all used the name of a Chinese port city in their names, such as Raohe, Fuyuan, Jixi City, Xunke, Tongjiang, and Donging, and that the official name of the companies also included the words “economic and trade,” “trade,” and “LTD”. The FBI further advised that recipient entities usually held accounts with a the Agricultural Bank of China, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and the Bank of China.

Fox-IT said its access to the gang revealed documents that showed members of the group establishing phony trading and shipping companies in the Heilongjiang province — Raohe county and another in Suifenhe — two cities adjacent to a China-Russia border crossing just north of Vladivostok.

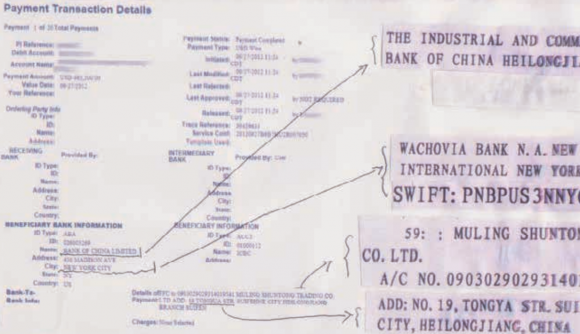

Remittance

slips discovered by Fox-IT show records of wire transfers that the

Business Club executed from hacked accounts in the United States and

Europe to accounts tied to phony shipping companies in China on the

border with Russia. Image: Fox-IT

“So it is not unlikely that peer-to-peer ZeuS associates would have made use of the positive economic climate and business friendly environment to open their businesses right there,” Fox-IT said in its report. “This shows that all around the world Free Trade Zones and other economic incentive areas are some of the key places where criminals can set up corporate accounts, as they are promoting business. And without too many problems, and with limited exposure, can receive large sums of money.”

Remittance

found by Fox-IT from Wachovia Bank in New York to an tongue-in-cheek

named Chinese front company in Suifenhe called “Muling Shuntong

Trading.” Image: Fox-IT

The red arrows indicate the border towns of Raohe (top) and Suifenhe (below). Image: Fox-IT

The Business Club regularly divvied up the profits from its cyberheists, although Fox-IT said it lamentably doesn’t have insight into how exactly that process worked. However, Slavik — the architect of ZeuS and Gameover ZeuS — didn’t share his entire crime machine with the other Club members. According to Fox-IT, the malware writer converted part of the botnet that was previously used for cyberheists into a distributed espionage system that targeted specific information from computers in several neighboring nations, including Georgia, Turkey and Ukraine.

Beginning in late fall 2013 — about the time that conflict between Ukraine and Russia was just beginning to heat up — Slavik retooled a cyberheist botnet to serve as purely a spying machine, and began scouring infected systems in Ukraine for specific keywords in emails and documents that would likely only be found in classified documents, Fox-IT found.

“All the keywords related to specific classified documents or Ukrainian intelligence agencies,” Fox-IT’s Sandee said. “In some cases, the actual email addresses of persons that were working at the agencies.”

Likewise, the keyword searches that Slavik used to scourt bot-infected systems in Turkey suggested the botmaster was searching for specific files from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs or the Turkish KOM – a specialized police unit. Sandee said it’s clear that Slavik was looking to intercept communications about the conflict in Syria on Turkey’s southern border — one that Russia has supported by reportedly shipping arms into the region.

“The keywords are around arms shipments and Russian mercenaries in Syria,” Sandee said. “Obviously, this is something Turkey would be interested in, and in this case it’s obvious that the Russians wanted to know what the Turkish know about these things.”

According to Sandee, Slavik kept this activity hidden from his fellow Business Club members, at least some of whom hailed from Ukraine.

“The espionage side of things was purely managed by Slavik himself,” Sandee said. “His co-workers might not have been happy about that. They would probably have been happy to work together on fraud, but if they would see the system they were working on was also being used for espionage against their own country, they might feel compelled to use that against him.”

Whether Slavik’s former co-workers would be able to collect a reward even if they did turn on their former boss is debatable. For one thing, he is probably untouchable as long as he remains in Russia. But someone like that almost certainly has protection higher up in the Russian government.

Indeed, Fox-IT’s report concludes it’s evident that Slavik was involved in more than just the crime ring around peer-to-peer ZeuS.

“We could speculate that due to this part of his work he had obtained a level of protection, and

was able to get away with certain crimes as long as they were not committed against Russia,” Sandee wrote. “This of course remains speculation, but perhaps it is one of the reasons why he has as yet not been apprehended.”

The Fox-IT report, available here (PDF), is the subject of a talk today at the Black Hat security conference in Las Vegas, presented by Fox-IT’s Sandee, Elliott Peterson of the FBI, and Tillmann Werner of Crowdstrike.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.